Maintenance in operational condition (MCO) is a vital element in the success of air operations. For the Air Force, the MCO transformation plan for assets and procedures is of primary importance and depends on synergy between military and industrial players.

Modernisation of the Air Force MCO Aéronautique

In January 2018, the Minister of the armed forces agreed a transformation plan aimed at improving the performance, efficiency and governance of Aeronautical maintenance in operational condition (Maintien en condition opérationnelle—MCO). MCO in the Air Force is of primordial importance, for it is an essential determining element in the success of any operation, a key factor in operational readiness and, perhaps less evidently, in the morale of personnel. The Air Force and all state and industrial players in the MCO structure are therefore fully mobilised to ensure the success of the plan and that it rapidly brings positive results within tightly controlled costs. For its contribution to this reform, the Air Force has initiated the NSO 4.0 project, which will look at modernising the level of operational support (Niveau de soutien opérationnel—NSO) within its field of responsibility to ensure the Air Force’s capability to fulfil all its missions in all places and in all circumstances.

MCO is not an end in itself—its sole objective must be to make materiel ready and in the right state for going into combat. It therefore contributes to airmen’s operational readiness, a direct responsibility of the Chief of the Air Staff (Chef d’état-major de l’Armée de l’air—CEMAA), and to the faultless conduct of the permanent missions of the Air Force—deterrence, permanent posture of security and various alert states—its commitments to external operations and its contribution to action in our overseas territories and in foreign countries.

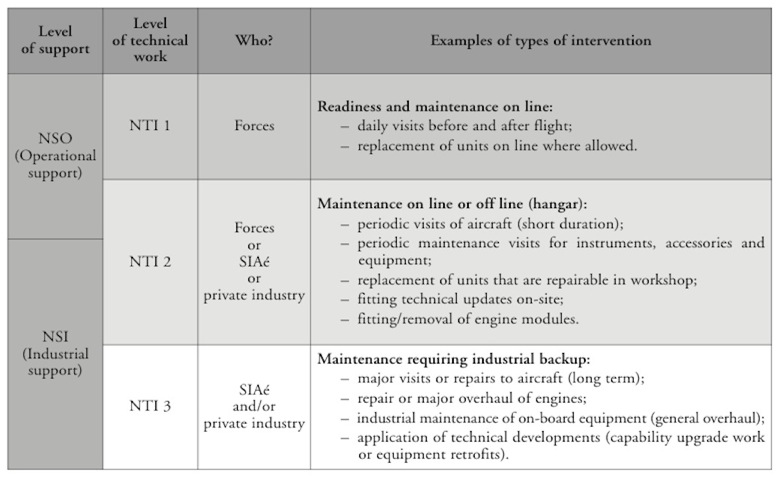

MCO consists of ensuring maintenance of equipment and integrating logistic functions (supplies, storage and distribution of spare and exchange parts) with technical functions (follow-up and handling of technical issues). Maintenance activities are divided into different levels of technical work (NT1, 2 and 3, where NT is Niveau Technique, technical level), and are carried out at two levels of support responsibility: the operational level (NSO), which is performed by the forces, and the industrial level (Niveau de soutien industriel—NSI) which for the state is performed by the Industrial aeronautical service (Service industriel aéronautique—SIAé). Private NSI is operated by private industries.

Success of this plan to improve MCO performance relies on a number of players with complementary responsibilities:

• Project managers (EMA, DGA, EMAT, EMM and EMAA(1)) prescribe the need(2) and allocate the financial and state-employed human resources. For the Air Force, CEMAA is responsible for the operational readiness of the forces placed under his authority and for the MCO of the materiel being operated. He exercises his responsibilities through the EMAA and the DRHAA.(3) Within this framework, the Major General of the Air Force (MGAA) is responsible for the air operational programme budget, of which 74 per cent is dedicated to the Materiel maintenance programme. The Air Force is also the employing authority and is also the responsible body for maintenance of airworthiness.

• Associate project management is delegated to the Directorate of aeronautical maintenance (Direction de la maintenance aéronautique—DMAé), which draws up an MCO strategy that ensures the overall coherence of MCO activity, and proposes it to the Chief of the Joint Staff (Chef d’état-major des armées—CÉMA). It also negotiates and steers maintenance contracts, and is responsible for part of the technical (OGMN,(4) authority for technical teams) and logistic (management of property and materiel, and end-to-end logistic coordination) functions. For budgetary issues it is responsible to the MGAA for steering the operational units’ MCO within the Air Force.

• The technical authority is the DGA, responsible for technical management of materiel throughout its life. For this, the DGA draws up with the forces a support strategy for each new fleet and takes on the initial support. Together with the DMAé, DGA is also responsible for keeping watch over and dealing with obsolescence.

• Project management for NSO is delegated to organic commands of each armed force, which employ their technical units and exercise in part the responsibilities of the OGMN and as a maintenance organisation. For the Air Force, the principal headquarters staffs in charge of the NSO are the CFAS and the CFA.(5)

• Project management for NSI is given to:

– SIAé, the state-owned operator, so that the Ministry for the armed forces can retain its expertise and capabilities for design and direct industrial-level intervention for industrial maintenance for which outsourcing is not possible or desirable. SIAé works on a number of fleets including those of the Air Force, both old (C-160 Transall, C-130H Hercules, Mirage 2000, Puma and Alphajet) and recent (A400M Atlas, Rafale), as well as on equipment that includes motors, electrical and mechanical assemblies, security, rescue and survival materiel, radomes and ground radars.

– A range of private sector industries that includes essential constructors and major aeronautical equipment manufacturers (Dassault, Airbus, Safran, Thales, MBDA and others) and also to top-ranking maintenance experts such as Air France Industries, Sabena Technics and TAP Air Portugal.

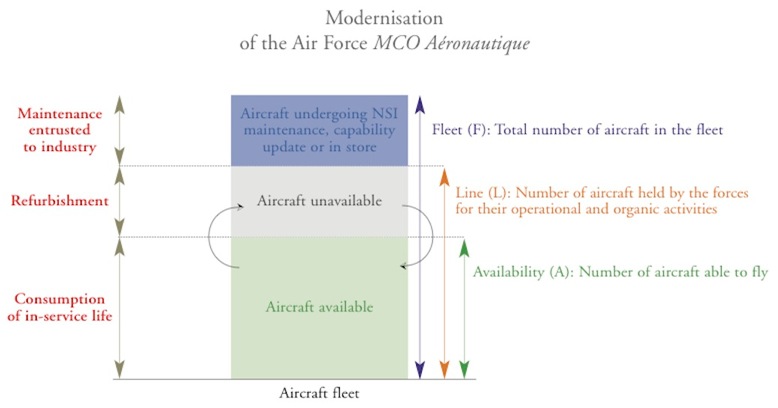

The overall performance of MCO depends on good coordination and the actions of each of the players. It is measured by results achieved in air activity, the amount of materiel made available to the forces (the line mentioned before), in daily availability and in control of cost. (See diagram below)

Within a given budget, air activity and availability are the most visible parameters of MCO performance. Activity comes from aircraft outfitted in the configuration needed for them to fulfil their mission—with laser designation pods and radar, for example. Other than its contribution to activity, availability contributes to the completion of all types of mission including maintenance of alert states and the various readiness states of the airborne component of the deterrent. The volume and quality of this air activity allows us to:

– Conduct air operations of prime importance: the permanent security posture, fight against Daesh in the Levant or against terrorism in the Sahel, retaliation strikes after the use of chemical weapons in Syria (Operation Hamilton(6)) and policing the sky over the Baltic are just some examples;

– Fulfil operational requirements that are demanding in terms of volume, range, reactivity and duration of action, such as protection of national territory, nuclear deterrence, knowledge and anticipation, crisis prevention and management, national emergencies and commitment to major operations;

– Ensure the operational readiness of crews so that they can carry out the above missions.

Achieving a balance here between NSO and NSI is essential to the performance of MCO. Keeping NSO correctly sized in relation to operational requirements is the guarantee that the Air Force can fulfil its missions in all places, in all circumstances and within cost limits. Close to the aircraft and fully focused on support of operational requirements, NSO contributes directly and decisively to the Air Force’s missions 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. It is staffed by military personnel, which counts much for its reactivity, autonomy, resilience and controlled cost, whatever the circumstances or theatres of operation.

To ensure this capability, the Air Force and its military personnel must continue to master a number of skills and essential knowledge, such as:

• The operation and maintenance of combat aircraft, some aircraft transport, special fleets and helicopters and also their equipment, armament and certain other material used in the aeronautical environment, the intensity of which varies with how each fleet is used and the skill level required.

• The operation and maintenance of aeronautical information and communication systems, including surveillance and approach radars, systems for operational command and control and ground-air defence equipment, following the same approach as for aircraft.

• Some logistic activity: here again within a boundary that depends on competences that are organically essential. In any case, commitment to external operations (Opération extérieure—OPEX) requires retention of military assets.

• Support of techno-logistical or embarked information systems.

• A level of technical expertise to contribute to maintenance and verification of airworthiness.

• Technical functions, comprising fleet management and organisation of tasks, and preserving associated capabilities for arbitration, in which the operational aspect must unquestionably remain primus inter pares. Behind this lies recognition of occasional inability to achieve the overall availability of assets to conduct priority missions. Keeping these functions within the Air Force is therefore logical and essential.

To judge by the very good levels of availability on OPEX, productivity of Air Force military manpower is very satisfactory.(7) Similarly, apart from OPEX, NSO performance in generating training activity is above 70 per cent, which means that for every ten aircraft held by the forces, seven can be put on line daily to contribute to an operational mission or operational training. Moreover, every military person working for NSO is also a combatant as well as a high-level technician. He or she divides active time between pure production, as it were, dedicated to MCO (80 per cent) and the requirements of military life (20 per cent).(8)

Since 2007 the Air Force has reduced its air manpower dedicated to aeronautical maintenance by 27 per cent through passing more MCO activity to private firms. NSO has been optimised and rationalised along the following lines:

• The boundary of NSO encompasses NTI1 activities and some NTI2 activities considered strategic for combat system fleets whose use is exclusively military: Rafale, Mirage 2000, Alphajet, C-130H and J Super-Hercules, C-160, C-135, CASA CN235, A400M, Puma, Fennec, AWACS and A330 MRTT (Multi Role Tanker Transport). Strategic NTI2 activity includes, for example upkeep of engines, mission equipment or OAE(9) that the forces would have to deal with themselves on OPEX. Retention of these technical skills means NSO incorporates certain types of preventive maintenance visit. This arrangement leads to deeper knowledge of the aircraft and involves activity that helps training of mechanics. It assumes high skill levels in the key repair activities essential for regenerating availability whilst on operations.

• The boundary of NSO focuses on NTI1 and some NTI2 activities for fleets that have very sensitive operational tasks but which are limited in number, or those which are technically close to their civilian equivalents, such as Caracal and the DHC6 Twin Otter, and soon the ALSR,(10) CUGE,(11) Reaper Block 5 and the European MALE drone (Medium altitude, long endurance).

• There is no NSO (i.e. all maintenance is passed to civilian industrial contractors) for the majority of flying training, strategic transport and governmental transport aircraft, including Grob G120, Embraer 121 Xingu, Pilatus PC-21, A310, A330, A340, TBM 700, Falcon and Super Puma.

The Ministry’s MCO transformation plan looked first at NSI, considered as one of the causes of under-performance to be treated as a priority.(12) On the basis of the report by IGA Christian Chabbert, this priority is being dealt with by seeking optimisation of contractual strategy with the following objectives:

– limit interaction between the different players (verticalisation);

– make industry responsible for a greater scope of activity (globalisation);

– give them greater visibility (long-term contracts).

This optimisation of contractual strategy could in some cases result in new transfers of NSO activity to the NSI. Nevertheless we need to look on a case-by-case basis at the impacts of such a move on operational effectiveness, which means ability to fulfil operational commitments, deployment capability and durability for example, and also on overall efficiency—extra costs weighed against against HR advantages.

With regard to its contribution to the transformation plan, and in pursuance of the NSO rationalisation effort made in recent years, the Air Force has initiated the NSO 4.0 project, which aims to identify new pathways for optimisation in accordance with the current MCO transformation plan. The work brings together all MCO actors, and has been entrusted to two Air Force NSO managers (CFA and CFAS), and is looking at the 3 principal areas of activity in the forces:

1. Production activity in the maintenance of aircraft;

2. Upkeep and operation of materiel used in the aeronautical environment;

3. Logistic movement.

Taking account of the many recommendations that have been made in all the audits, enquiries and special studies on MCO, particularly those arising from IGA Chabbert’s report, the NSO 4.0 project covers four principal headings:

1. Organisation, aimed at consolidating organisations, notably by precise definition of the limit of the NSO baseline in terms of the HR, technical assets and skillsets to be retained.

2. Sequencing, aimed at improving coordination of all MCO players on air bases, by better association of industrial concerns whilst keeping within the forces the responsibility for decision-making, which ultimately has to be guided by the rhythm and demands of operations.

3. Lean Management, to delete low-value tasks, optimise the sequencing of maintenance operations, recover training margins and follow the best industrial standards.

4. Performance measurement, aimed at consolidating tools for performance measurement, verifying project results and the effectiveness of actions.

Management of change is a fundamental aspect of this major project. In particular, getting personnel on board is a strategic challenge, and to respond to that the following four areas in particular will be developed: communication; look-ahead management of workforce, jobs and skills; partnerships (with education, private industry and state MCO actors) and innovation.

The spirit of innovation will be aided by the NSO 4.0 project’s use of opportunities arising from technology, reviewing of processes and organisations and constitution of a live network within technical units. This network will be linked to action initiated by the recently launched Agency for defence innovation (Agence pour l’innovation de Défense—AID) so that budding new ideas can blossom and bear fruit.

* * *

MCO is a major element of the armed forces’ capability to attain their required level of readiness and fulfil their operational commitments. Its success comes from the motivation and commitment of all the players concerned and who contribute to it. With regard to its cost, we need to take up every opportunity offered by technical innovations, organisational changes and possible optimisation in order to keep cost under control yet without reducing the capability of the forces to Se Préparer, Agir et Durer.(13) ♦

(1) État-major des Armées (Joint Staff), Direction générale de l’Armement (Procurement organisation), État-major de l’Armée de terre/de la Marine/de l’Armée de l’air (Army, Navy and Air Force Staffs respectively).

(2) Covers a number of documents including the Objectives and performance contract (Contrat d’objectifs et de performance—COP), which together define the needs and priorities of the forces.

(3) For MCO the Air Force HR directorate (DRHAA) manages operational staff as part of operational support or on behalf of other employers within the Ministry.

(4) Organisme de gestion du maintien de la navigabilité des aéronefs d’État (OGMN)—Organisation for the maintenance of airworthiness of aircraft belonging to the state.

(5) Commandement des Forces aériennes stratégiques (CFAS)—Strategic air forces command; Commandement des forces aériennes (CFA)—Air forces command.

(6) See the article by Lieutenant Colonel Moyal in this volume, p. 47-52.

(7) The availability on OPEX is over 80 per cent overall and even over 90 per cent for combat fleets.

(8) Combat training, exercises, missions and permanence, among others.

(9) Organes, accessoires et équipements. (Instruments, accessories and equipment, mentioned in the table above).

(10) Avion léger de surveillance et reconnaissance (Light surveillance and reconnaissance aircraft).

(11) Charge utile de guerre électronique (EW payload), future system to replace Transall C-160 Gabriel.

(12) For the Air Force, this means C-130H, Puma, Mirage 2000, A400M and some equipment, such as laser designation pods.

(13) This is the motto of the Air forces command (Commandement des forces aériennes—CFA), meaning [approximately] ‘prepare, act and remain’.