The United States is a multi-dimensional power with a systemic air advantage in the Indo-Pacific region. Nevertheless, the hybrid action conducted by the Chinese Air Forces, especially around Taiwan, is gradually redefining the regional balance.

US Air Power in the Indo-Pacific Region

The Indo-Pacific is a vast geopolitical region which encompasses the two eponymous oceans and which extends from Eastern Africa to the American continent. It is first and foremost a semantic contrivance developed by several governments with the aim of limiting the growing presence of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in the region. Thought of even in the 1930s by the German geopolitician Karl Haushofer,(1) the notion reappeared in the writings of the former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in 2007.

The term soon came into general use in various chancelleries, those of Australia (2013), the United States (2017), and India and France (2018) in particular. Whilst each interprets and characterises the region according to his own interests, the extent of the China-centric concept is well understood. The PRC’s main partners—Russia, Pakistan, Iran and North Korea—do not use this terminology directly despite their considerable influence in the region. On the other hand, the United States and its historical allies were the first to make use of it. The appearance of the description Indo-Pacific as a geopolitical space of reference underlines a new Sino-American duopoly in international relations.

In general, when one thinks of the Indo-Pacific the maritime aspect comes first to mind since the region encompasses 60 per cent of the world’s oceans, some 233 million square kilometres,(2) and yet the airspace above it is a further fundamental component of the multi-dimensional aspect of US power in the area. Through its Indo-Pacific strategy, Washington seeks to develop key sectors, including its power projection capability, permanent bases in allied countries, access to military installations, international cooperation between air forces and civil and military export markets.

The United States still has a systemic air advantage over China in the region, though the hybrid action conducted by Chinese air forces is gradually redefining the balance of power.

The United States of America—an Indo-Pacific Power

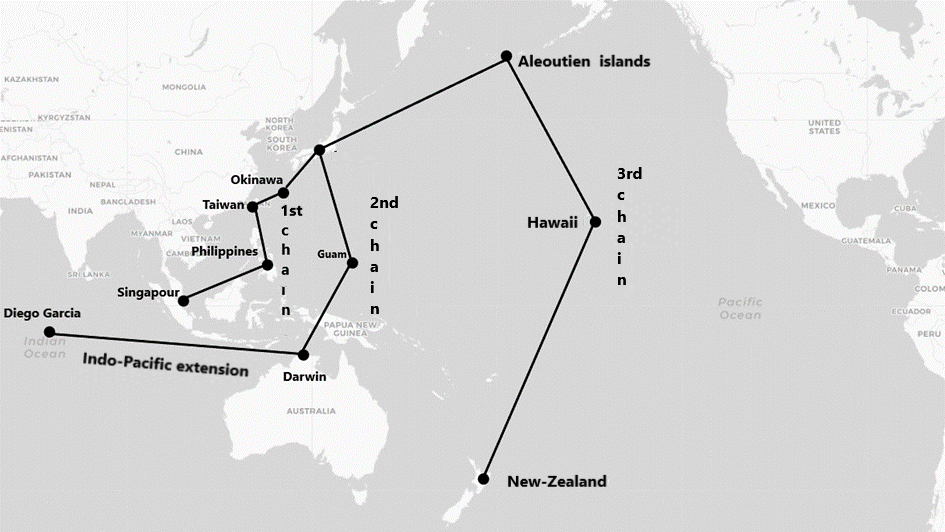

The United States has long been a power in the Indo-Pacific region. From the 19th century, the federal government developed a high-seas capability and extended its influence to the whole of the Pacific Basin—to Japan in 1853, Midway in1867 and the Philippines, Hawaii and Micronesia in 1898. Even before the United States entered the Second World War in 1941, the US Navy was a blue-water force, capable of being projected anywhere on the high seas. During the Cold War, the Secretary of State John Foster Dulles envisaged the containment of communist forces by a system of three arcs of circles—the island chain strategy—off the coastline of Eastern Asia. Washington still has sovereignty over eleven US territories in the Pacific Ocean(3) and through the Compact of Free Association has links with the Republic of Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia and the Republic of the Marshall Islands.

In the Indian Ocean, the military base of Diego Garcia, which became part of the British Indian Ocean Territory in 1965, has been let to US forces since 1971. It is an important logistic and operational base, notably used by B-2 Spirit bombers as a departure point for raids on Iraq in 1991 and 2003, and Afghanistan in 2001.

© Paco Milhiet, 2023. Source: Kulshrestha S. (RADM Retd.), Cupping the Pacific—China’s Rising Influence, Unbiased Jottings on Global Maritime Issues, 27 March 2018 (https ://skulshrestha.net/2018/03/27/cupping-the-pacific-chinas-rising-influence).

The Emergence of a US Indo-Pacific Strategy

As a consequence of Barack Obama’s ‘rebalance to Asia’ strategy of 2011, the US Administration progressively adopted the terminology. Even in 2010, in a speech to representatives of the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN)(4) Hillary Clinton, then Secretary of State, highlighted the importance of the Indo-Pacific Basin. Think tanks and major analysts also gradually accepted the vocabulary(5) and later President Donald Trump made the strategy his own in a speech during a meeting of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) in Vietnam in November 2017.(6) Since then the various ministries and authorities concerned have consistently referred to the Indo-Pacific in statements on geopolitical matters concerning Asia and the Indian and Pacific Oceans. The transformation in 2018 of the US Pacific Command (PACOM) into Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM) was official recognition by the military authorities of this evolution in vocabulary. The change of Administration on the election of Joe Biden in 2021 has not altered the broad principles of US foreign policy, particularly regarding the Indo-Pacific region. Notwithstanding the divisions within US society, it would seem that in terms of foreign policy and more specifically in the face of Chinese development, there is geopolitical continuity in the White House.

Extension of the Indo-Pacific into Other Strategic Schemes

To keep the initiative on the strategic narrative US diplomacy has devised complementary forums even more overtly directed against Chinese expansion in the region, such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD), a multimodal partnership of the United States, Australia, India and Japan, and AUKUS, the new tripartite military alliance of the United States, Australia and the United Kingdom.

The increased number of divisive strategic schemes coincides with intensified US criticism of the Chinese regime,(7) something on which Republicans and Democrats agree. Should a crisis situation arise between the two superpowers, the principal manoeuvres will probably be conducted from the air.

Airspace, a Space of Confrontation in the Indo-Pacific

The United States has dominated international relationships since 1945 through the strength of its foreign trade and military power. Over the same period, the phenomenal growth in aviation has transformed international relations by playing a dominant role in contemporary conflicts, at the same time contributing to the globalisation of trade and movement of people.

The US Air Force and other elements of the US armed forces are the guarantors of US domination through the use of their air assets in support of Washington’s foreign policy. The advent of Chinese competition, especially its capability in the air, is a sign of a new duopoly developing in the Indo-Pacific region, and in particular around the island of Taiwan, for long the main stumbling block there.

US Air Diplomacy in the Indo-Pacific

US air diplomacy is an extremely wide-ranging subject and insofar as it involves the use of air assets in support of foreign policy(8) it is applied in various ways in the Indo-Pacific.

First, in terms of military might, the USAF has nearly 330,000 personnel on active service,(9) and over 5,200 military aircraft, which make it the biggest air force in the world.(10) Aircraft of the US Army (4,409), US Navy (2,464) and US Marine Corps (1,157) add to that figure to give a total of 13,247 aircraft, which is more than the next 5 air fleets in the world put together (all of which border the Indo-Pacific).

Number of military aircraft in the armed forces by Country

|

|

Air |

Army |

Navy |

Marine troops |

Total |

|

United States |

5 217 |

4 409 |

2 464 |

1 157 |

13 247 |

|

Russia |

3 863 |

nc |

310 |

/ |

4 173 |

|

China |

1 991 |

857 |

437 |

/ |

3 285 |

|

India |

1 715 |

232 |

239 |

/ |

2 186 |

|

South Korea |

898 |

611 |

69 |

17 |

1 595 |

|

Japan |

746 |

392 |

311 |

/ |

1 449 |

|

Pakistan |

810 |

544 |

32 |

/ |

1 386 |

|

Egypt |

1 053 |

nc |

nc |

/ |

1 062 |

|

Turkey |

612 |

398 |

47 |

/ |

1 057 |

|

France |

570 |

306 |

179 |

/ |

1 055 |

In the Indo-Pacific region INDOPACOM has 375,000 military personnel (of which 46,000 are USAF) and 2,500 aircraft operating from US Pacific bases in Hawaii, Alaska, California, Guam, Micronesia and Diego Garcia. US forces can also rely on a network of forward bases in foreign countries (in Japan, 45,000 personnel on the bases of Misawa, Kadena and Yokota, another 22,000 on the South Korean bases of Osan and Kunsan and 2,500 personnel in Darwin, Australia). They also have access to certain military installations in the Philippines and in Singapore. Furthermore, the USAF organises a number of bilateral exercises with Asian air forces and participates in major multilateral exercises in the area to boost interoperability and develop politico-military relations.(11)

Arms sales are a further basic element of US air diplomacy. The United States is the biggest arms exporter in the world. These sales are not devoid of politico-strategic interest and moreover they help standardise training and doctrine of use. Where technology transfer becomes involved, the agreements go beyond simple sales of equipment and take on a geopolitical element regarding long-term protection and the spread of operational culture and technological seasoning.(12)

Armed forces in the Indo-Pacific region remain largely dependent on weapon systems imported from foreign suppliers; indeed, the biggest arms importers in the world are to be found there.(13)

Regional Classification of Arms Importing Countries

|

Country |

Millions of dollars spent from 2016 to 2022 |

% of Imports from USA |

|

India |

21,122 |

9.5 |

|

Saudi Arabia |

20,129 |

75 |

|

Qatar |

10,386 |

45.5 |

|

Egypt |

10,169 |

72 |

|

Australia |

9,135 |

71 |

|

China |

8,741 |

unknown |

|

South Korea |

7,114 |

66 |

|

Pakistan |

6,750 |

1 |

|

Japan |

5,666 |

96 |

|

United Arab Emirates (UAE) |

5,412 |

65 |

|

Vietnam |

2,820 |

4 |

|

Singapore |

2,767 |

40.7 |

|

Indonesia |

2,721 |

24 |

|

Thailand |

1,984 |

10.5 |

|

Bangladesh |

1,964 |

0,5 |

|

Philippines |

1,731 |

16 |

|

Myanmar |

1,556 |

unknown |

|

Taiwan |

1,114 |

99 |

|

Malaysia |

890 |

4.6 |

Clearly, the Indo-Pacific is a favoured export market for the US DITB. The main purchasers of US arms are also their main political partners, though the reverse is also true—the countries with which the United States does not maintain good relations do not buy its arms. For example, the F-16, the most-sold combat aircraft in the world,(14) has been bought by over 20 countries, notably South Korea (171, produced locally under licence), Indonesia (36), Singapore (60), Thailand (68) and Taiwan (142). More recently the fifth-generation combat aircraft, the F-35 developed by Lockheed Martin and in service in the US forces since 2015, has been sold to Australia (72 on order), Japan (145), Singapore (4) and South Korea(40).

The United States still has a significant air power advantage over its main opponent in the Indo-Pacific: China. Nevertheless the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) is developing hybrid strategies which could in time pose a threat to some US allies in the area and overcome US military and technological superiority.

Chinese Air Force deployments around Taiwan

The airspace around China is subject to growing geopolitical challenge. In addition to the territorial conflicts in the China Seas the island of Taiwan, claimed by Beijing but supported politically by the United States, crystallises regional tensions. Since 1979 Washington has ceased to guarantee military intervention in case of Chinese invasion of Taiwan, instead maintaining a deliberate strategic ambiguity(15) on what American reaction to Chinese aggression might be in order to prevent unilateral annexation of the island. The trilateral relationship between China, Taiwan and the United States is therefore both complex and sensitive: the least politico-diplomatic incident threatens to upset the status quo.

The most recent crisis was on 3 August 2022, when Nancy Pelosi, third in the order of US protocol, arrived in Taipei on board Air Force One. Her visit was seen in Beijing as an intolerable provocation, and provoked the launch of eleven DF-21 ballistic missiles into the area around the island, of which 5 overflew Taiwanese territory. In the same period, a hundred combat aircraft and ten warships crossed the median line in the Strait of Taiwan, an unofficial border tacitly accepted since 1955. These manoeuvres of a hitherto unseen magnitude are now classified as the 4th Taiwan Strait Crisis.(16)(17) Since that date the PLAAF has increased its incursions beyond the median line.

Crossings of the median line by Chinese aircraft

Drawn by Paco Milhiet, 2023, source: Ben Lewis, Taiwan ADIZ Violations (https://docs.google.com/).

The PLAAF now operates in a grey area, operations hovering between peace and war which fog the distinction between a permanent air security posture and overtly aggressive action in order to destabilise the Taipei regime. Given that the virtual border of the median line is now defunct, the next crisis is likely to see a greater intensity of Chinese provocation.

Conclusion

The United States still enjoys overall air superiority in the Indo-Pacific region. Were there to be any military escalation involving the two great powers, the Chinese Air Force would probably not venture beyond its immediate neighbourhood.

Nevertheless, by way of the repeated incursions of the PLAAF close to Taiwan, the Chinese authorities are sending a clear message: the time when US forces had an asymmetrical advantage in the Strait of Formosa is past. The People’s Republic of China is now able to bring many assets to bear, air assets in particular, in launching an overall offensive on Taiwan. Any foreign involvement in defending the island will be at a high material and human cost. ♦

(1) Li Hangsong, The “Indo-Pacific”: Intellectual Origins and International Visions in Global Contexts, Modern Intellectual History, vol. 19, n° 3, September 2022, p. 807-833 (https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479244321000214).

(2) Peron-Doise Marianne, Indo-Pacific, le maritime, (The Maritime Indo-Pacific) Les Grands Dossiers de Diplomatie n° 53, October-November 2019, published again in Asie Pacifique News, 12 January 2020 (https://asiepacifique.fr/Indo-Pacific-le-maritime-marianneperondoise/).

(3) Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Johnston Atoll, American Samoa, Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Island, Kingman Reef, Midway Atoll, Wake Island and Palmyra Atoll.

(4) Clinton Hillary, Secretary’s speech–America’s Engagement in the Asia-Pacific, Honolulu, 28 October 2010 (https://2009-2017.state.gov/).

(5) For example, KAPLAN Robert in America’s Pacific Logic, Stratfor Analysis, 2012, http://www.stratfor.com/analysis/americas-pacific-logic.

(6) Trump Donald, Remarks by President at APEC CEO Summit, Da Nang (Vietnam), 10 November 2017 (https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/).

(7) Of note, the Congress convened a Select Committee on the CCP (Chinese Communist party) to achieve bi-partisan consensus on the threat posed by the PRC and to develop an action plan to defend the American people.

(8) Lespinois (de) Jérôme, Qu’est-ce que la diplomatie aérienne ? (What is air diplomacy?) ASPF Afrique et Francophonie, 4th Quarter 2012 (https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/).

(9) Department of Defense, 2021 Demographics, Profile of the military community, (https://download.militaryonesource.mil/).

(10) Flight International, 2022 World Air Forces, (https://www.flightglobal.com/download?ac=83735).

(11) For example, Garuda Shield (Indonesia), Cope Tiger (Thailand), Keris Strike (Malaysia) and Cope India.

(12) Zajec Olivier, Les industries d’armement et le commerce des armes, (Arms industries and the arms trade) Questions internationales n° 73, 2015, p. 70-74 (https://medias.vie-publique.fr/).

(13) Beraud-Sudreau Lucie, Liang Xiao, Wezeman Siemon T. and Sun Ming, Arms-production Capabilities in the Indo-Pacific Region: Measuring Self-reliance, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), October 2022 (https://doi.org/10.55163/XGRE7769).

(14) Flight International, op. cit.

(15) Kuo Raymond, ‘Strategic Ambiguity’ Has the U.S. and Taiwan Trapped, Foreign Policy, 18 January 2023.

(16) The first three crises in the Strait were in 1954, during the armed conflict over the Tachen Islands, in 1958 with the shelling of the islands of Kinmen and Matsu, and in 1996 when the United States deployed two naval-air groups in the Strait in response to Chinese missile firings.

(17) Danjou François, La 4e crise de Taiwan. Quels risques d’escalade ?, (The 4th Taiwan crisis. What are the risks of escalation?) Question Chine, 6 August 2022 (https://www.questionchine.net/).